Psychology Research

Mathematical Intuitions

In 2017 I joined the Lab for the Developing Mind at NYU to research a simple question: can people tell whether a path connecting two points on the surface of a sphere is the shortest path between the points? It’s not as easy at it seems! We have all seen pictures of planes taking surprising routes across the globe.

Get this: the red route is faster by plane than the yellow route.

The reason is fairly straightforward: on a sphere (like the Earth), the shortest distance between two points is the path which, if it were to continue all the way around the sphere, would slice the sphere in half. This is called a geodesic or great circle. This map of a flight between New York and Madrid gives a good sense for how you find this great circle distance between two points.

Constructing a great circle: a path which, if continued, would slice the circle in half.

In our study, we showed children and adults pictures of two points on a sphere, with two different options of paths between them. They had to pick the shorter path. For example, they might see this:

Which of these paths is shorter?

I already told you how this works, so you know the answer is the path on the right, which would slice the circle in half. How about this one:

Which of these paths is shorter?

Should be fairly straightforward: the path on the left will wrap around the circle, whereas the one on the right will slice off a little cap. Notice this unusual situation: even though the path on the right looks “linear”, it’s not the shortest path between the two points on the sphere. On a sphere, the “straight line” between two points is actually curved.

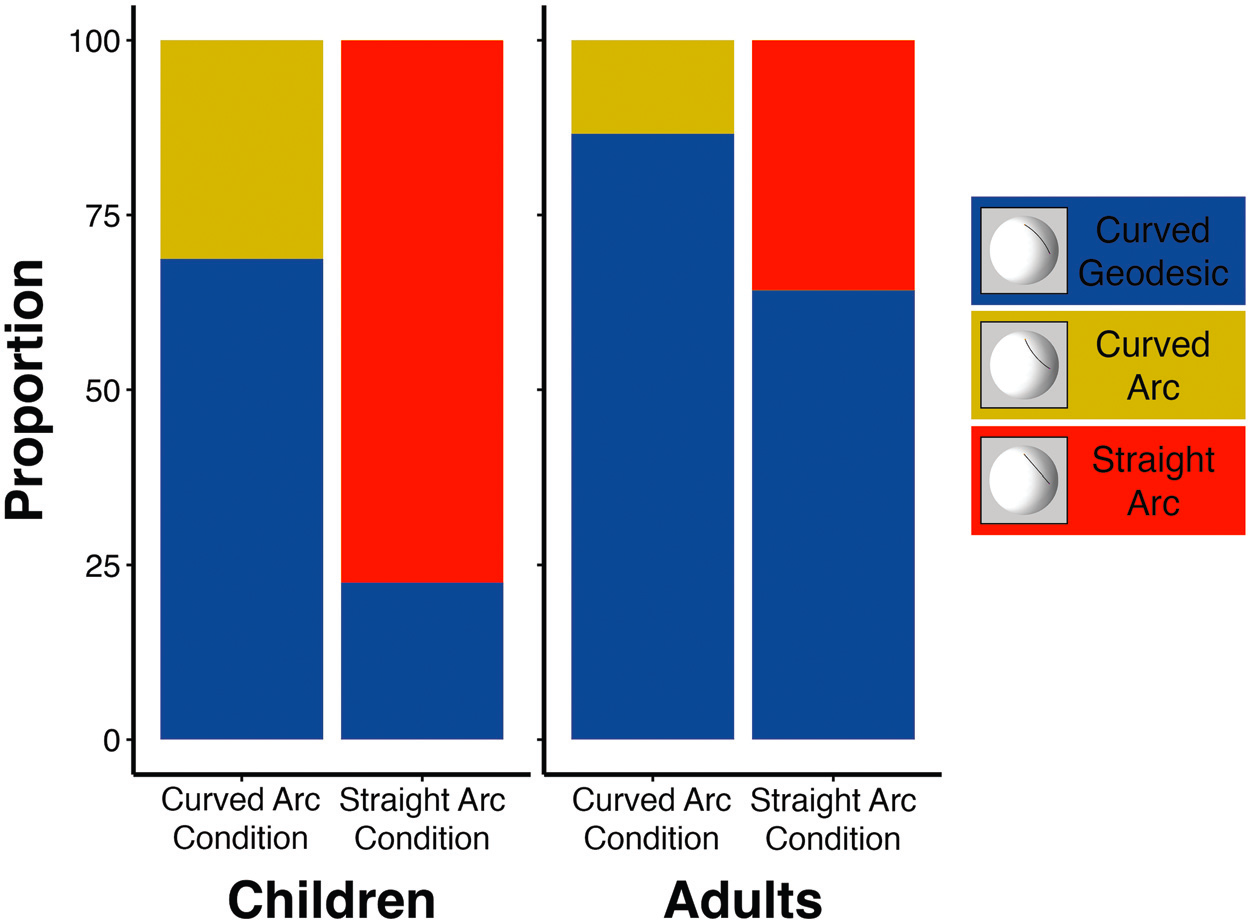

So how did kids and adults do at this task? Generally speaking, quite well! When shown two curved paths, as in the first example above, both kids and adults were quite good at identifying the correct response: kids were correct 70% of the time; adults 87% of the time. However, when shown a curved path compared to a straight one, the kids fell for the trap: they thought the straight-looking path was the shorter one 23% of the time. Adults fell for it too, but impressively, still got it right 65% of the time. Here is all of that information in a graph.

Conclusion: Children and adults are both pretty good at spherical geometry, but children get fooled when a straight line is involved.

All of this was written up into a formal scientific paper. Here’s the official citation.

Huey, H., Jordan, M., Hart, Y., & Dillon, M. R. (2023). Mind-bending geometry: Children’s and adults’ intuitions about linearity on spheres. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001509.

Email me if you don’t have access to the paper and want a copy!

Huey, H., Jordan, M., Hart, Y., & Dillon, M. R. (2023). Mind-bending geometry: Children’s and adults’ intuitions about linearity on spheres. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001509.

Email me if you don’t have access to the paper and want a copy!

Morality and Emotion on Twitter

During my Master’s degree, I came across a study showing that tweets with moral-emotional language are more widely shared. Moral-emotional language refers to words like “disgust”, “shame”, and “hate”—words that have a moral connotation (make an ethical judgement) and an emotional connotation (express a feeling).

Moral words (left) make an ethical judgment; emotional words (right) express a feeling. Moral-emotional words (center) do both.

Moral words (left) make an ethical judgment; emotional words (right) express a feeling. Moral-emotional words (center) do both.The 2017 study showed that for each additional moral-emotional word in a tweet, the tweet would receive 20% more retweets. The study was gaining some traction at the time, complemented by Molly Crocket’s work on moral outrage. I was a bit of a skeptic. I had spent the prior year deeply invested in the replication crisis, and had joined ReproducibiliTea, a journal club in Oxford. I decided that for my Master’s thesis, I would attempt to replicate the study, and see if merely adding moral-emotional words to a tweet really make it more likely to be retweeted.

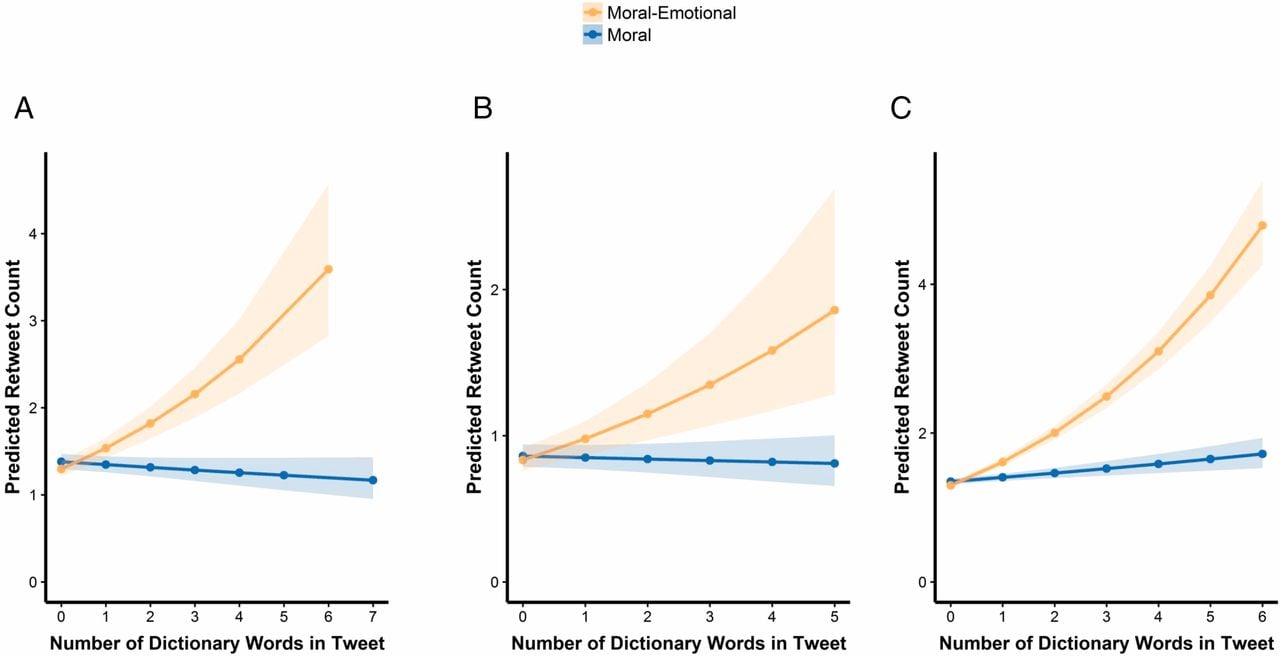

Here’s how the original study worked. They collected tweets on three topics: same-sex marriage, gun control, and climate change. They found these tweets by using certain keywords (e.g. “NRA”, “gay marriage”, “global warming”) and scraping Twitter for 20-40 days. They then ran statistical analyses to see the relationship between retweets and the presence of moral, emotional, and moral-emotional words. The result was this graph:

Here’s how the original study worked. They collected tweets on three topics: same-sex marriage, gun control, and climate change. They found these tweets by using certain keywords (e.g. “NRA”, “gay marriage”, “global warming”) and scraping Twitter for 20-40 days. They then ran statistical analyses to see the relationship between retweets and the presence of moral, emotional, and moral-emotional words. The result was this graph:

It’s a very neat result: moral words do not lead to more retweets, but moral-emotional words consistently do.

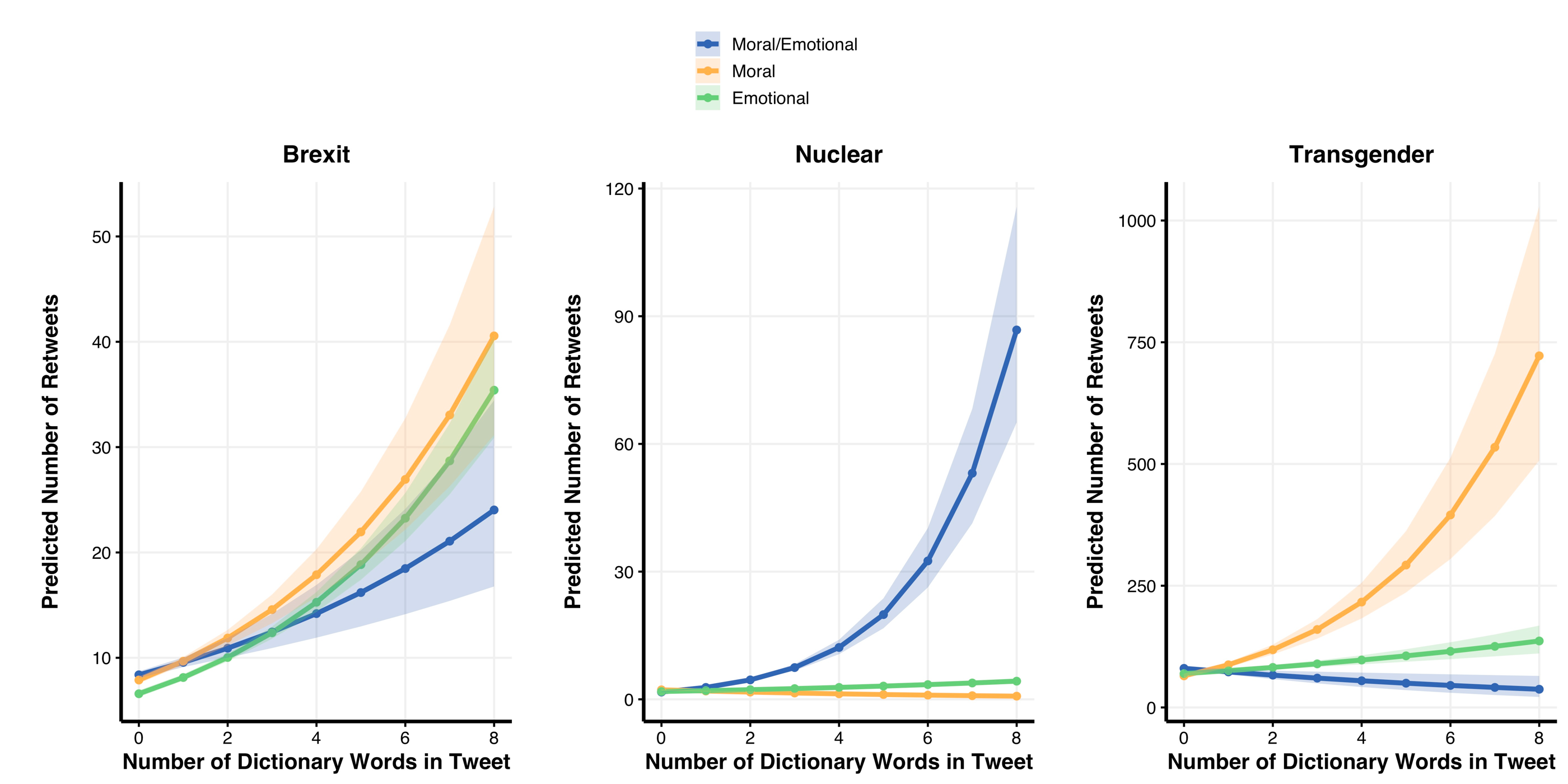

The goal of my thesis was to replicate these results, except I chose three different topics: Brexit, nuclear power, and transgender rights. Aside from the subject matter (and the keywords I used to find tweets about the topics), my methodology was otherwise identical. Here was my final result:

The goal of my thesis was to replicate these results, except I chose three different topics: Brexit, nuclear power, and transgender rights. Aside from the subject matter (and the keywords I used to find tweets about the topics), my methodology was otherwise identical. Here was my final result:

Not quite as clean! There were no consistent relationships for any of these topics or words. For Brexit, every kind of word increased retrweets; for nuclear, moral-emotional words did the trick (the only clear replication of the original study), and for transgender, only moral words increased retweets. So while the general pattern still held, and while there is definitely something to be said about the relationship between moral & emotional language and retweets, I personally am a skeptic of any straightforward claim about how this stuff works.

For more info about my Master’s thesis, check out the Open Science Foundation page or you can download the PDF.

For more info about my Master’s thesis, check out the Open Science Foundation page or you can download the PDF.

Speech Errors

It is a truth universally acknowledged that when people make speech errors, the errors are more likely to be real words than gibberish. You’re likely to say “darn” in place of “barn”; you’re unlikely to say “plock” in place of “clock”. We know this because of experiments where we give people tongue twisters and try to elicit speech errors. In these experiments, errors are more likely to be real words.

My undergraduate thesis asked the question: is this also true when the error is a swear word? Can we elicit speech errors that are also swear words? We did this by asking people to read error-prone phrases like “kiss pick” (very liable to result in accidental inappropriate word) or “kit pick” (liable for an error, but a G-rated one) and seeing how the two compared.

Turns out people do not like to swear. They were significantly more likely to stop their speech utterances when they were at risk of saying a swear word, relative to how often they made a regular ol’ speech error.

I am now deeply suspicious of just about every aspect of this study. I’m suspicious of the statistical methods. I’m suspicious of the tiny sample size. I’m suspicious of the idea of getting undergraduate students to swear. I would take almost nothing in here as scientifically valid. But it was fun to do at the time!

Here’s the full paper.

My undergraduate thesis asked the question: is this also true when the error is a swear word? Can we elicit speech errors that are also swear words? We did this by asking people to read error-prone phrases like “kiss pick” (very liable to result in accidental inappropriate word) or “kit pick” (liable for an error, but a G-rated one) and seeing how the two compared.

Turns out people do not like to swear. They were significantly more likely to stop their speech utterances when they were at risk of saying a swear word, relative to how often they made a regular ol’ speech error.

I am now deeply suspicious of just about every aspect of this study. I’m suspicious of the statistical methods. I’m suspicious of the tiny sample size. I’m suspicious of the idea of getting undergraduate students to swear. I would take almost nothing in here as scientifically valid. But it was fun to do at the time!

Here’s the full paper.